by Mx Watson | Jan 13, 2025 | Blog peliculas

I swear to retain from personal taste, I am no longer an artist

I swear to refrain from creating a work as I regard the instinct is more important than the hole

my supreme goal is to false the truth out of my character’s and settings

I swear to do so and all the means available and at the cost of any good taste or any considerations

FACT CREATES NORMS AND TRUTH ILLUMINATION

by Mx Watson | Jan 12, 2025 | Blog pensamientos, Blog pintura

“Singularity”

Pintura, grabado y cera sobre madera

36,5 x 28 cm

2020 Berlin, Alemania

12 Enero 2025, Berlín

Queridx Xxxxx,

He elegido esta obra para tí porque la he realizado durante una meditación acompañada por una amiga de mi infancia que ahora es especialista en Arte Terapia y dedica su vida a ofrecer puentes de conexión a lo espiritual mediante la práctica artística. Asistí virtualmente a uno de sus cursos y durante el mismo se originó el comienzo de ésta pintura. Ella indicó hacer un círculo y luego de meditar dentro de él, colocar un punto central dentro del mismo, que no debía estar en el centro necesariamente, y a partir de ese punto percibir nuestra energía.

Esta fue la primer obra en blanco y negro sobre madera que realicé en Berlín. Antes de ella trabajaba en obras en color sepia sobre madera, influenciadas por mi viaje a Escocia. En cambio, durante el workshop, algo me indicó que tome solo estos dos colores. Esta pintura es el inicio de mi estancia en Alemania en el año 2020. Era abril y ya hace un mes esperaba noticias para saber si podría volver a mi país debido a las restricciones del Covid-19. Durante ésta espera sucedieron cosas muy profundas como ésta pintura.

La llame “Singularity” porque así se llama en términos de la ciencia física a la concentración de masa que se encuentra dentro de los agujeros negros que se encuentran en el espcio. Dichos fenómenos me atraen profundamente dado a que es solo hace pocos años que se descubrió que son los que mantienen en movimiento al espacio, y que el mismo se encuentra en constante expansión elio-centrífugo debido a las fuerzas que la “masa oscura” opera en el tiempo-espacio que percibimos.

Es de mi especial interés el hecho de que el conocimiento de la comunidad más antigua de nuestro planeta, los aborígenes australianos, mejor llamados “the first nations people”, incluye a la “Oscuridad” como el elemento de observación central. Es a ésto a lo que se referían, sin saberlo científicamente. Su lectura de los cielos nocturnos era regida por las formas que tomaba esta oscuridad y no por la luz de las estrellas. Es interesante que un pueblo tan antiguo pudiese saber que las estrellas brillan porque reflejan una muerte a años luz de distancia, y que es en la oscuridad en donde están las huellas de la vida. Ellos a ésto lo llaman “Dark Emu”.

Personalmente y por mi interés humanístico, encuentro que ésta comprensión de lo Oscuro es más liberadora que las posturas iluministas post-europeas en la que se mira al humano como un ser al que se debe corregir desde la mente, aludiendo a “la luz de la mente” y relegando a la oscuridad a todo aquello que no puede ser controlado por la razón. Esto ha generado un impacto en nuestra sociedad. No me extraña que vivamos una post-contemporaneidad con los sentidos tan apagados. Siempre tuve preferencia por la mirada Oriental acerca del balance de las energías como única manera de realmente poder descifrar el conocimiento que cada ser humano trae al mundo. Solo en el balance se puede interpretar con profundidad, aceptando la energía que proviene de “lo desconocido”, que sencillamente es aquella a lo que la mente no puede poner palabras o circuitos de análisis que le permitan hacer uso de esa información.

De la misma manera, nuestra ciencia llama “masa oscura” a la maza que moviliza al espacio porque aún no se han escrito las teorías indicadas para entenderla. Oscurecemos lo que no entendemos, pero la verdad es infinita, nada real puede ser amenazado.

Esta pintura se titula “Singularity” porque manifiesta un pacto de confianza conmigo mismo acerca de aquella verdad alrededor de la cual transitan mis energías, psicología, historia humana y proyección social. Observandola de lejos, pasa a ser de la humanidad. Realizar esta pintura fue para mi un acuerdo conmigo mismo. Aún no sabía para qué, y quizás aún no lo sepa, pero es mejor así. Todas las personas tenemos un centro gravitacional de energía, llamado el “Alma”. A mi me gusta llamarlo “Singularidad”.

Tu apoyo significa para mí otro compromiso hacia mí mismo, y es por eso que siento que merece materializarse entregándote ésta pintura.

Con mucho cariño,

Mx Watson

by Mx Watson | Jan 6, 2025 | Blog M. Lopez, Blog pensamientos, Blog pintura

Oscuridad es la decisión de no amar, en tajadas, momentos, planos, raspones, para definirse. Difundirnos en la eternidad es la condición humana. Nos definios egos seres, y nos defendemos. Nos decimos ser, de una u otra manera. Me resuelvo a no serte para desearte que seas de aquella u otra manera, así como me decido a serte, deseándote, así la suerte nunca sea mía. Te deseo al comprenderte, te sostengo al pronunciarte. Más la oscuridad también está en mí. Estas letras flotan en una pantalla negra. Te tecleo porque te creo.

Jo

by Mx Watson | Nov 18, 2024 | Blog fotografía

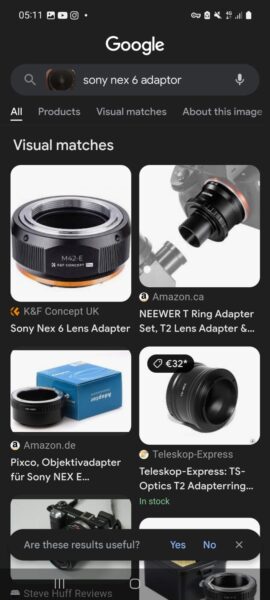

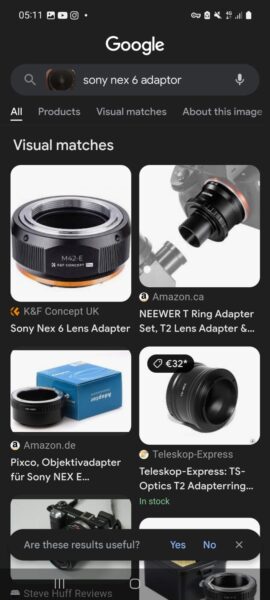

Lamentablemente el lente kit que venía con la cámara Sony Nex-6 de 16-50 OSS se rompió. Parece ser que este lente es muy deliado en el mecanismo del zoom, el cual parece ser una pieza de plástico, a diferencia de todas sus demás piezas. El plástico sufre más los cambios de temperatura, humedad, movimientos y tb puede quebrarse. Rip querido Lente.

A razón de ésto, y gracias a lo cual agendamos el encuentro con Nico, mi especialista en fotografía especializado, empezamos a ver opciones que se ajusten a mi presupuesto.

- Empezaremos por buscar alguna subasta de un lente parecido a éste, sino el mismo modelo, para tener como lente básico automático.

- Compraré un adaptador para los lentes de la cámara Konica que econtré y que registré en este post. Estos lentes no conectarían con la función automática de la cámara, haciendo que me tome más tiempo controlar la distancia focal y manejar de manera manual la apertura de la cámara. Esto me resulta un desafío interesante! Me permitirá estudiar mejor la ténica.

- Dentro del futuro posible tendría que conseguirme un mejor lente como este. Este lente salió en el año 2023 con una versión mejorada muy recomendada. Ahora esta fuera de mi presupuesto, pero quien sabe en cuanto pueda lo consigo:

https://cameradecision.com/lenses/review/Sigma-18-50mm-F2.8-DC-DN-Contemporary-E-Mount

by Mx Watson | Nov 17, 2024 | Blog M. Lopez

Fenómeno modelo

Mi piel se arruga

Sonrisa franca

Franquismo

Cordeles roídos

Soy tu oído

Mientras saltas

Mi realidad

La realidad

Te sonrío

Tu cadera marca

Paso de carretas

Destruídas

La policía

Se te escapa

Será la lujuria

Quién se salva

La que debe lo que vive

Solitariamente

Puede

M. Lopez

by Mx Watson | Nov 17, 2024 | Blog M. Lopez

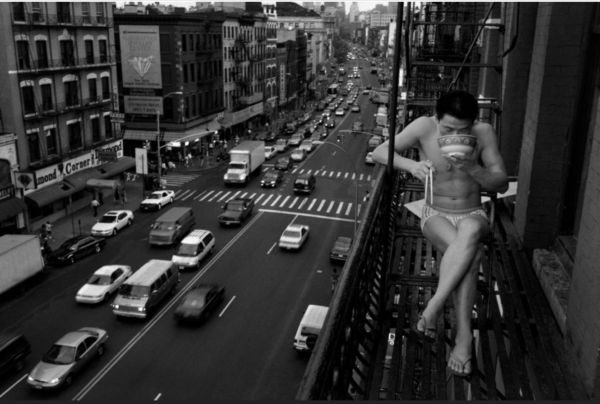

“I am in the middle of your picture”

I am going back home, bike on the M10

A cab drives you through Frankfurter Tor

El metro dobla sobre la imágen

Mido la distancia focal

Enfocamos opuestos

No tan diversos

Sino no nos encontraríamos

Enredados en este mundo

Que es tan difícil

La mirada presiona

Imprimi3ndo

La realidad en la si3n

Nos escondemos

De la necesidad (de amar)

Las ciudades s3guirán

Construyéndose hacia arriba

Clases arriba

Clases abajo

Culturas al costado

Basura en Taiwán

¿A donde vamos con todo esto?

A veces no lo puedo soportar.

Te mueves

Me voy

Corredores

Corriendo

M. López

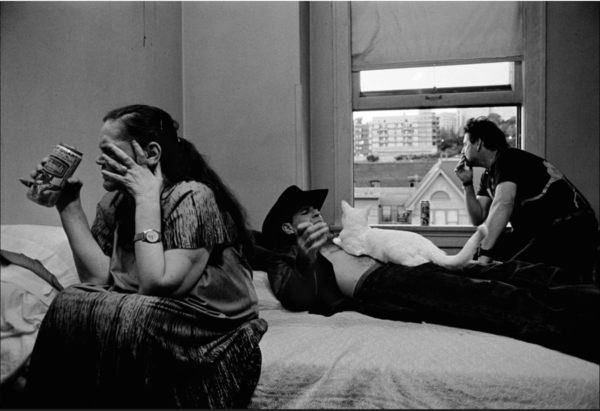

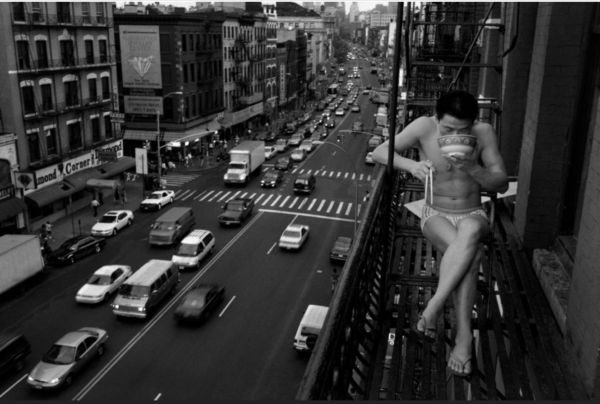

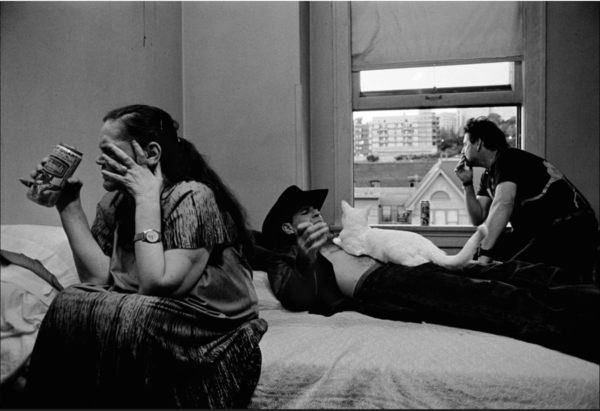

by Mx Watson | Nov 16, 2024 | Blog fotografía

From:

https://pro.magnumphotos.com/C.aspx?VP3=CMS3&VF=MAGO31_10_VForm&ERID=24KL53ZLJS